Rear Admiral Robert Carthew Reynolds: 30 July 1745 – 24 December 1811

The Memorial

The Sculptors and likely origin of Memorial.

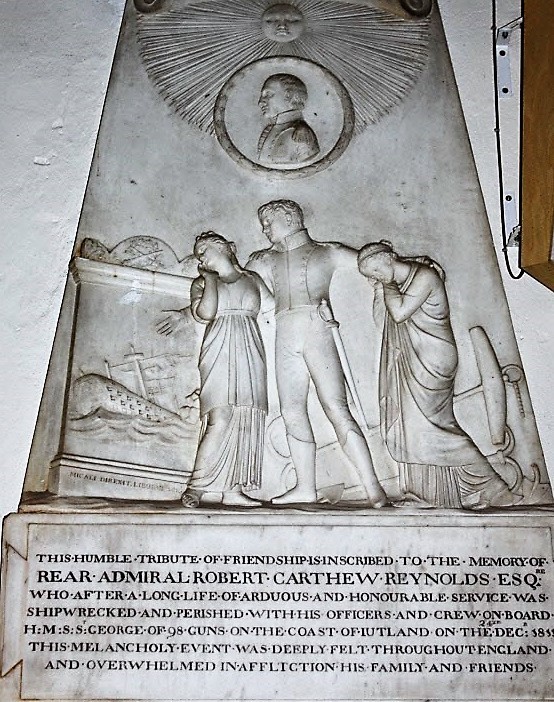

The memorial to Rear-Admiral Robert Carthew Reynolds is a fine example of decorative and monumental sculpture, probably produced in the workshops of Livorno near Florence from the fine marble of Carrara. The work and design is attributed to Micali. Possibly, this attribution may be open to speculation. In the early nineteenth century, the Micali family, based in Livorno, were historians and merchants, engaged in transport, and there is no available evidence to date, that they produced fine works of art[1].

During this period, the fine art trade was very strong. Sculptural and monumental pieces in Carrara marble were transported particularly to the USA and Britain, with many craftsmen and artists involved. Examples would be the Baratta family – father and son – who produced masterly originals as well as replicas of famous sculptured pieces, as did Antonio Canova [1757-1822]. Their reputations were well-known in Europe, and it is easy to understand why such a memorial would have been ordered from this region.

The monument to Rear-Admiral Robert Reynolds has a medallion-portrait and below it, the relief of a young soldier pointing to a memorial with a depiction of a naval battle (1). The work, curiously, is signed ‘Micali direxit Liburni 1816’ instead of the more usual ‘fecit.’ The Micali family owned the largest alabaster workshop in Leghorn and specialised in copies from antiquity. Many of their customers were visitors to Italy. They had long-standing connections with the British. In 1787 Josiah Wedgwood wrote to one of the family asking him to assist John Flaxman RA, a ‘much-valued friend of mine who is going to make some residence in Italy’ (Smiles 1894, 221). Equally strong connections were held with the French, including Empress Josephine who was a customer in 1810, and with American visitors. Charles Micali was charged with the execution of the important Tripoli monument to six American naval heroes, carved in Leghorn, 1806-7, and shipped to the Academy at Annapolis, where it still stands. The family was also active in Carrara and the workshop was still functioning in 1826.

The Life of Rear Admiral Robert Carthew Reynolds

Overview: Rear-Admiral Reynolds was a highly respected officer of the British Navy, who served in four wars over a career spanning 52 years. He died in 1811 during a terrible storm which scattered the convoy and wrecked three ships of the line including his own flagship St George. More than 2000 sailors were drowned, including Reynolds.

Home Life in Cornwall and the British Navy:

Rear Admiral Reynolds was born in the village of Lamorran in Cornwall in 1745 and joined the Navy when aged fourteen years. He served under Captain Edgecumbe during the Seven Years War, notably at the Battle of Quiberon Bay. During the 1760s, he moved on to serve as a midshipman in HMS Venus and became a lieutenant in 1770. During the American War, Reynolds was involved in action aboard HMS George, HMS Barfleur and HMS Britannia in the Channel Fleet.

Over the next few years, Reynolds turned attention to his private life. He married Jane, daughter of John Vivian, at Cardinham, Cornwall on 7 December 1779. The family settled into a new home built on the site of a seventeenth century house at Penair, in the northern part of St Clement Parish, Truro. They raised three children, among others lost in infancy, including two sons, both of whom joined the Navy. The elder son, Robert was killed in action against the French in 1804.

Reynolds was next called to sea in 1795, when tumultuous times in revolutionary France again raised tensions. He was given command of first ‘The Amazon’ and next ‘The Indefatigable’, performing with sound success against the French. During this period, he took with him his younger son Barrington. Barrington was aged nine when he joined the Navy as a servant, and was destined to achieve a very prestigious and long career.

Trading, War and Weather in the Baltic

During the early years of the nineteenth century, the threat from Napoleon and the expansion of the French Empire was ever present. Protection of the Channel and its trading ports was of prime importance. In particular, it was necessary to secure the support of the Danes in keeping the seaways open to British ships and securing supplies.

The primary source of naval stores was in Scandinavia and Russia with convoys travelling via the Baltic and North Sea. The route was known to be treacherous with shallow depths and plenty of waves, incoming from the Atlantic and created by shallows. Any hint of a gale was likely to endanger a ship by driving it onto the neighbouring coast. This was the situation that faced Reynolds on Christmas Eve 1811.

Three years before, in 1808, Reynolds had been made a Rear Admiral, and in 1810 was ordered to the Baltic Sea on HMS St George. The following year, a large convoy left Sweden bound for England. The convoy consisted of 130 merchant ships, escorted by HMS St George, flying the flag of Rear Admiral Robert Carthew Reynolds.

Bad fortune followed. In mid-November 1809, there was a strong gale that hit the convoy as it lay off Bornholm Island. Approximately 30 merchant ships were wrecked, when they were driven aground. One large merchant ship broke free of anchors and cutting across the St George, severed her anchor cable. The captain, Oliver Guion, immediately ordered the other anchors to be cut away to allow the ship to be sailed, but the increasing storm drove her towards the shore. The captain next wanted to remove the masts to stop the ship drifting further, but Admiral Reynolds was reluctant to agree to such action, and inevitably the St George was driven onto the shore, losing its rudder. Later it was towed into Wingo sound at Goteburg. HMS Hero and HMS Grasshopper were ordered to join the convoy and escort them home.

The St George was fitted with a temporary rudder, and commentators at the time pointed out that the St George was now in a parlous state and needing many repairs, after long service. However, the convoy was reassembled and accompanied briefly by another convoy escorted by Dreadnought, Orion, Vigo and Victory.

Then once more, disaster struck. On 19 December, a strong gale hit the convoy. Cressy managed to remain close to the St George and reported that the ship was in a bad state. The storm returned on 23 December and the Captain of the Cressy decided to move out to sea, farther from the coast. No signals were received from St George in response, where all hands appeared to be engaged in saving the ship. The Defence remained close by, as the captain felt it was his duty to support the St George.

On Christmas Eve, 1811, the St George and the Defence were thrown onto the rocks on the coast of Jutland. Both ships were destroyed by the waves. Of the 865 officers and men on the St George, only 12 survived. Only 6 men out of 560 crew of the Defence, made it to shore. Rear Admiral Reynolds was seriously injured and died above deck, some hours after the collision. His body was not found. The deck was washed away by high waves and it is likely that his remains were interred along with some 2000 others in the dunes of Jutland at Thorsminde.

The St George

[1] For example, Giuseppe Micali [1768-1844], was a very eminent historian who promoted the idea of a federalist state in Italy with diverse and ancient cultures, restoring a sense of pride and purpose to Italian identity